The key to increasing standard of living is increasing labor productivity

Unpacking this counterintuitive conclusion

Standard of living doesn’t have a strictly agreed-upon definition, but for the sake of anchoring on something, let’s use “the level of income, comforts, and services available to an individual, community, or society” (Wikipedia).

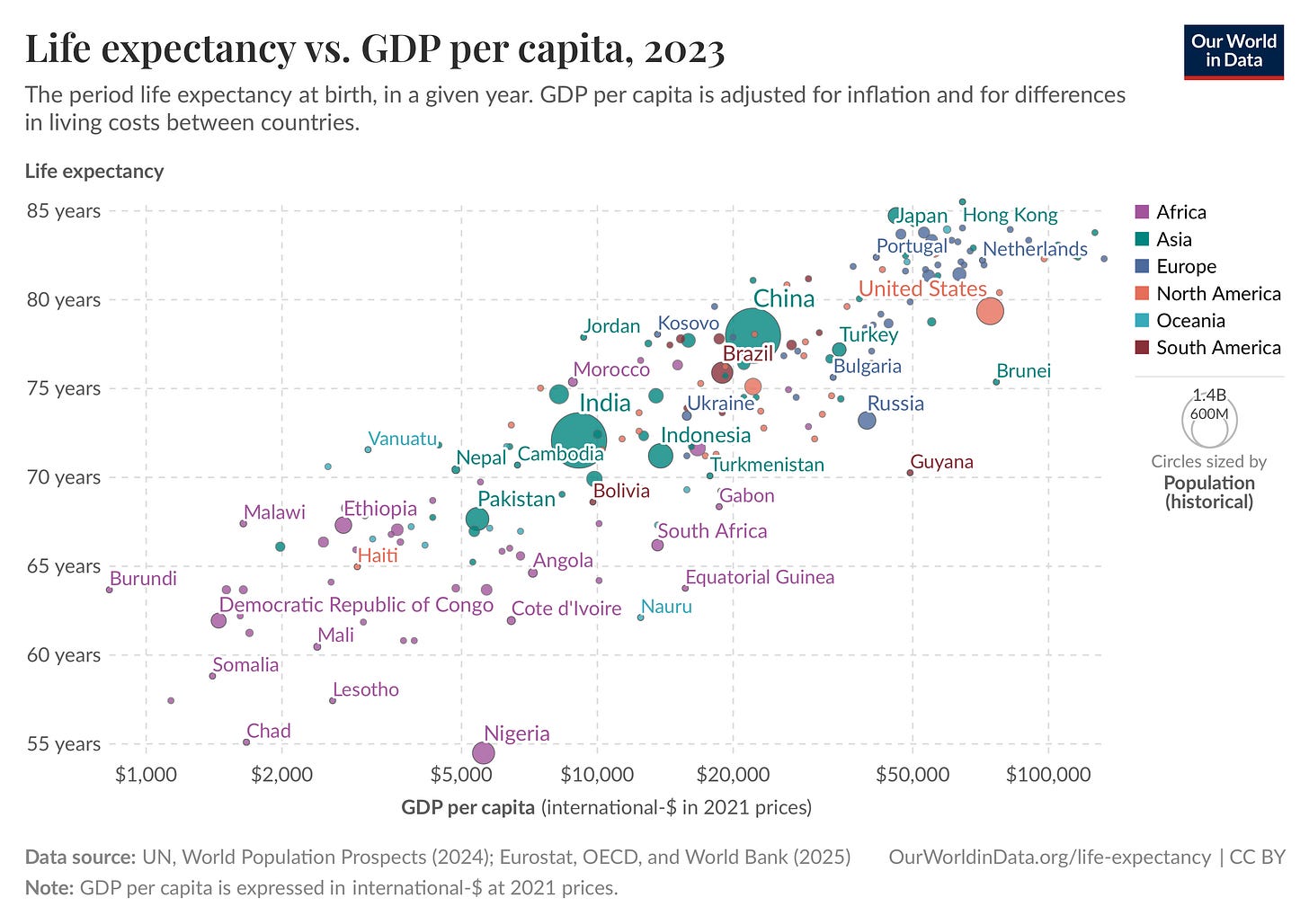

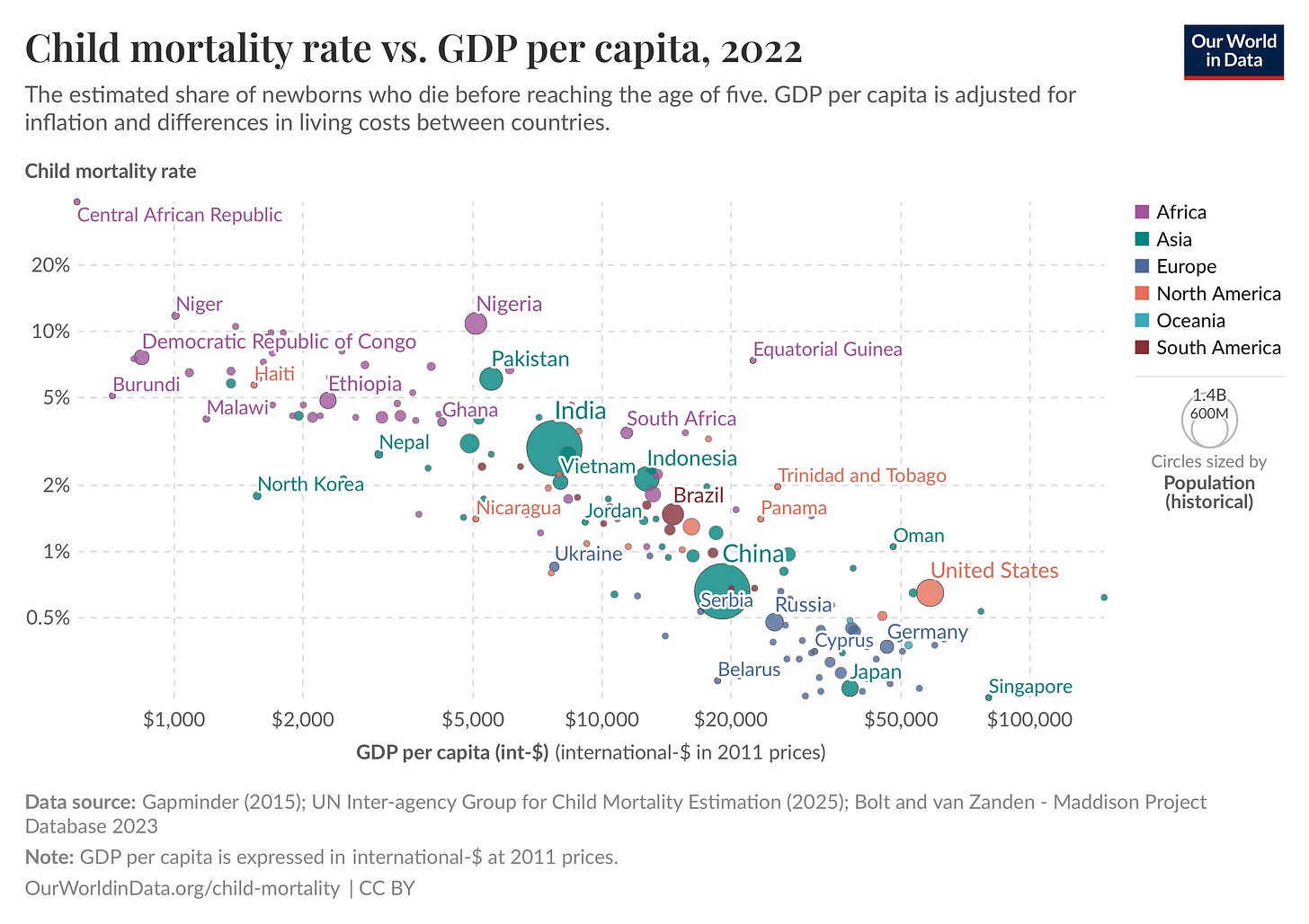

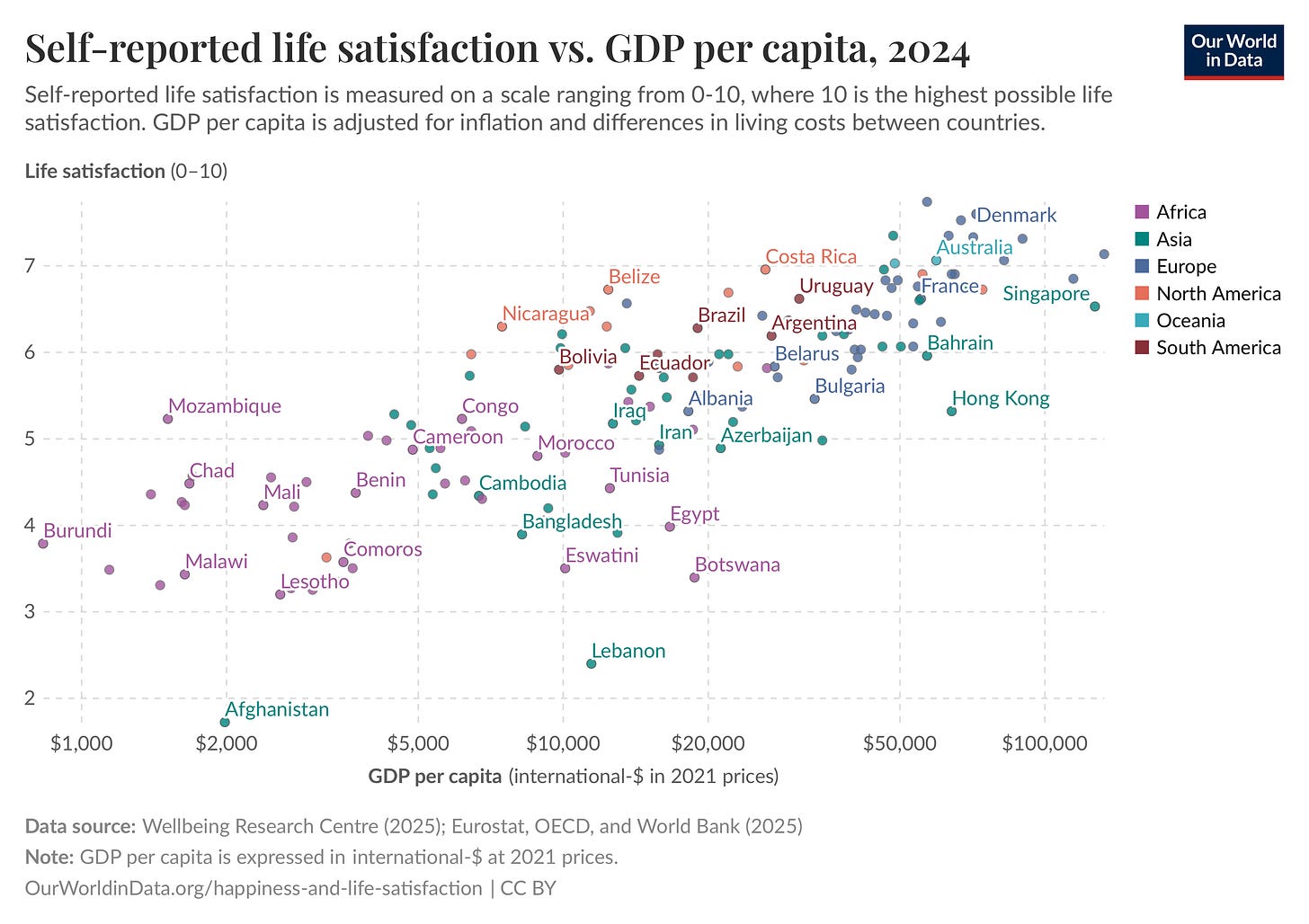

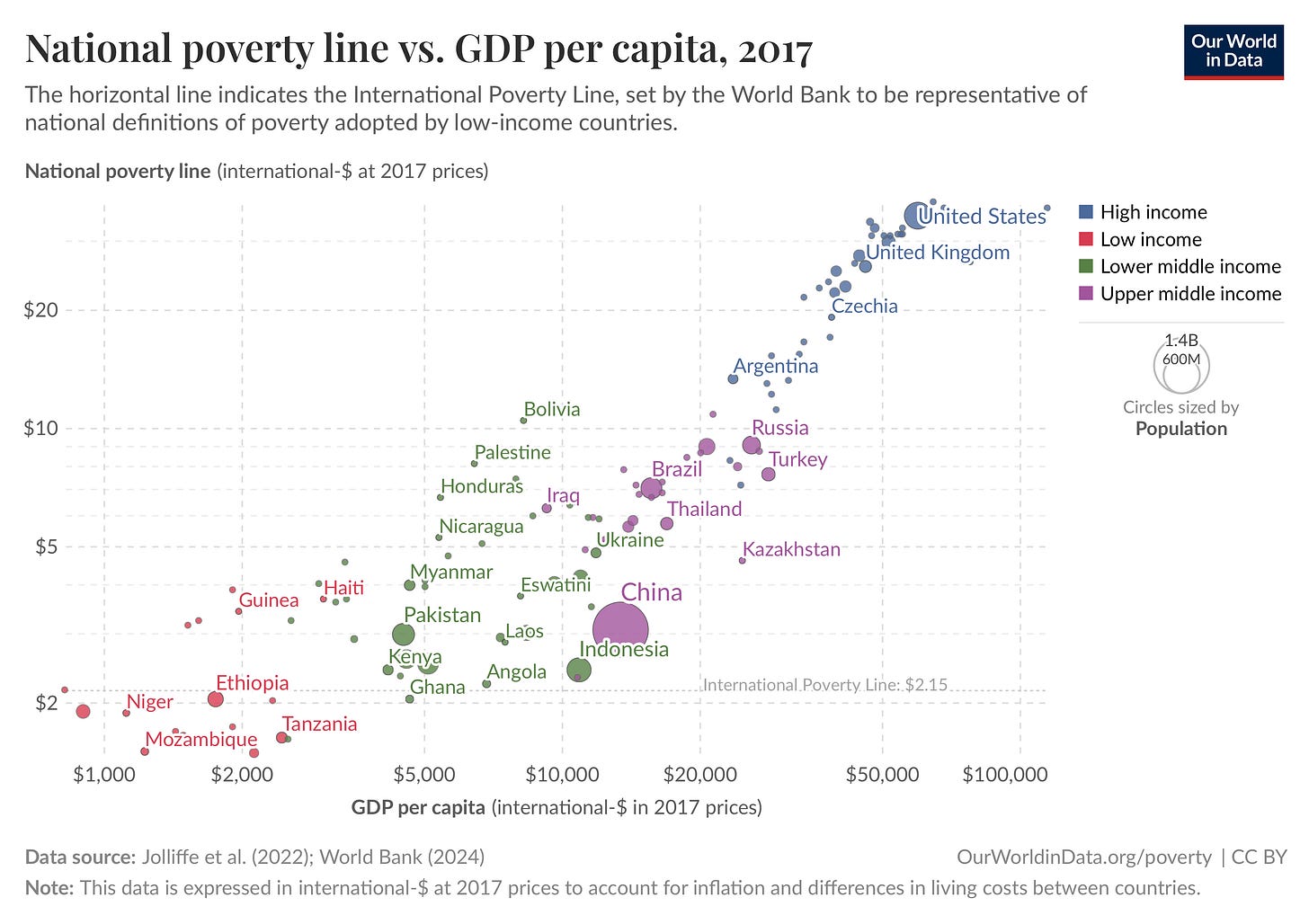

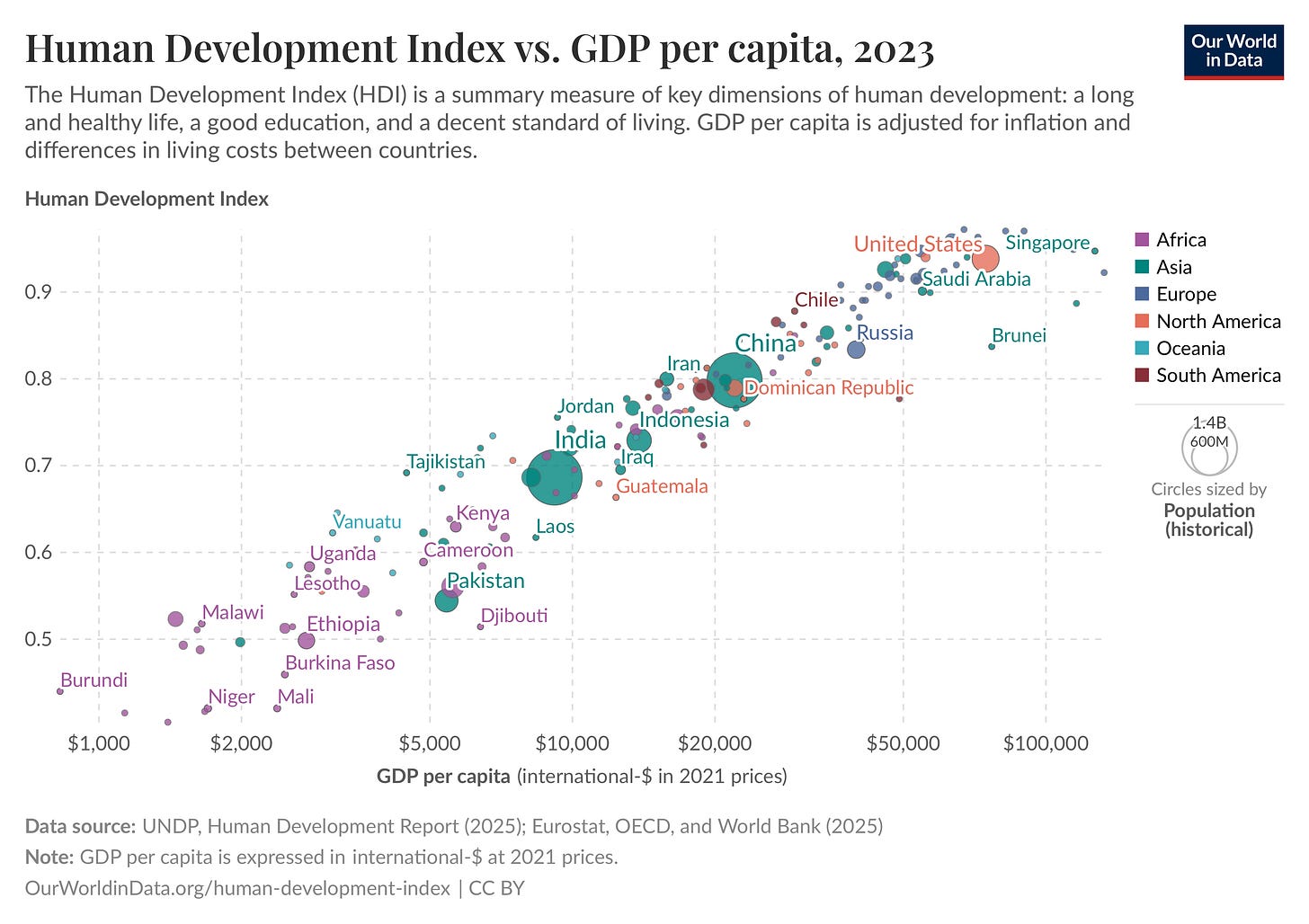

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, that is, the average economic output per person in a country, is often used as a proxy metric to compare the standard of living across countries. Of course, this proxy metric, being solely about money, doesn’t directly capture non-monetary aspects of standard of living associated with quality of life or well-being. However, most of these non-monetary aspects are tightly correlated with GDP per capita, rendering it a reasonable proxy.

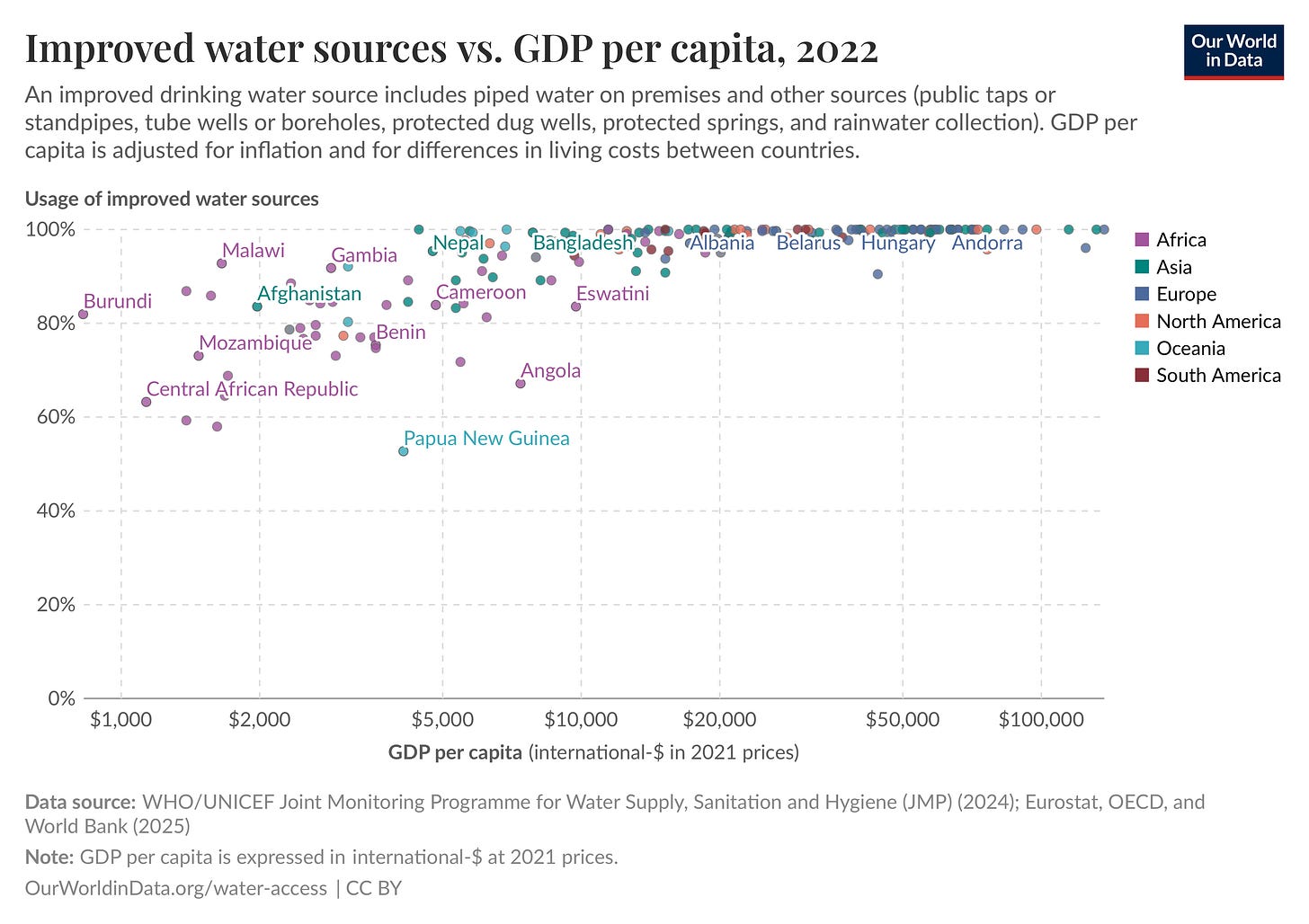

Our World in Data features numerous plots of such measures against GDP per capita. Here are a few of the ones people tend to care about most:

These measures are clearly tightly correlated to GDP per capita, as are common aggregate measures such as the UN’s Human Development Index that combines lifespan, education levels, and GDP per capita.

These tight correlations are somewhat intuitive because GDP per capita by definition means more money to buy things, and that includes buying more healthcare, education, leisure time, and luxiries, which one would expect to be correlated to healthspan, life satisfaction, and other measures of quality of life and well-being.

Nevertheless, at some level of GDP per capita, you reach diminishing returns for a given measure, and we would then expect the corellation to cease for that measure. For example, here is access to clean (“improved”) water sources, which maxxes out at medium incomes after you reach 100% since you can’t go higher than 100% on this measure.

However, we haven’t seen that yet for the most important measures like life expectancy, the poverty line, and self-reported life satisfaction. All of those can go higher still, and are expected to do so with further increases to GDP per capita, certainly for lower GDP-per-capita countries (climbing up the existing curve) but also for the U.S. (at or near the fronteir). In other words, with enough broad-based increases in income, many are lifted out of poverty, the middle class is more able to afford much of the current luxury and leisure of the rich, and the rich gets access to whatever emerges from new cutting-edge (and expensive) science and technology.

We should continue to watch and ensure these correlations remain tight. But as they remain tight, I think it is safe to say right now that we would expect increases in standard of living to be tightly correlated with increasing GDP per capita. While there are other necessary conditions like maintaining rule of law, broadly giving people more money to buy better healthcare, education, and upgraded leisure time should increase standard of living. That part is pretty intuitive.

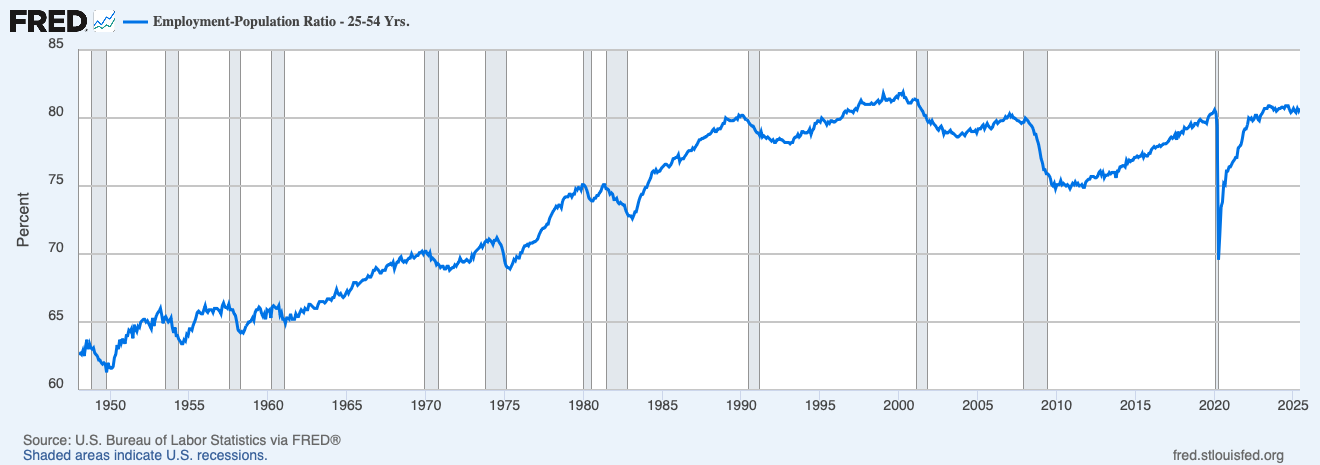

What’s not intuitive is how to do so. You can’t just print money, because that results in inflation. It has to be increases in real income, that is, after inflation. So, how do you do that? If you’re a country where a large % of the working-able population doesn’t currently have a job, the easiest way is to find those people jobs. Unfortunately, that won’t work for the U.S. anymore since most everyone who wants a job has a job. It worked for a while through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s as ever greater %s of women entered the workforce, but then plateaued in the 1990s.

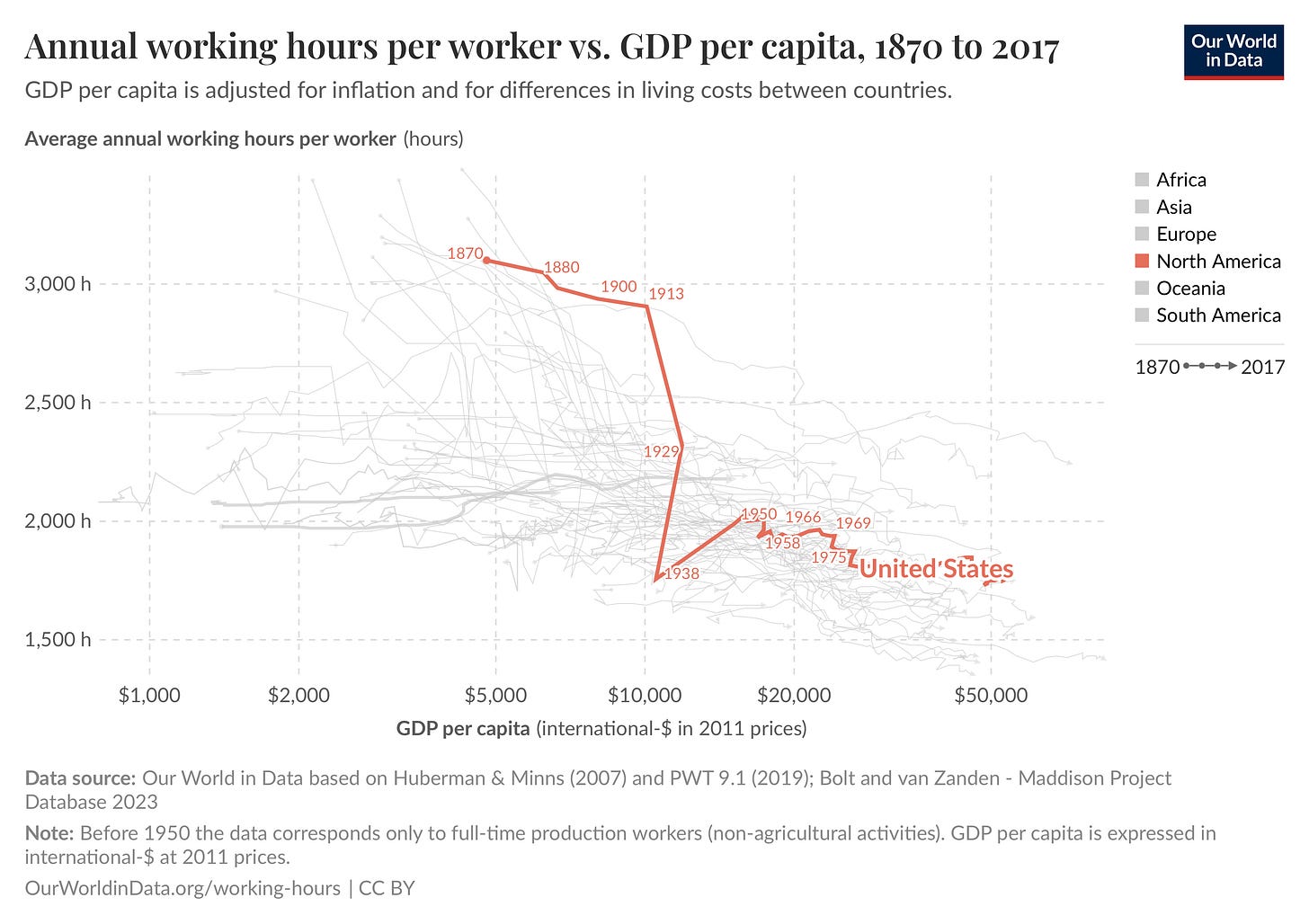

You could try to get people with jobs to work more hours (and therefore make more money per person), but that also doesn’t work for the U.S. since we already work a lot relative to other frontier countries, and as people get more money they seem to want to work less, not more. For example, in the U.S. we’re working a lot less hours per worker than we did in 1950, let alone 1870. This makes intuitive sense since quality of life and well-being can’t get to the highest levels if you’re working all of the time.

That leaves upgrading the jobs people already have in the form of higher income for the same amount of hours worked. And this means, by definition, increasing labor productivity, which is the amount of goods and services produced per hour of labor. To pay people more without triggering inflation, they also have to produce more output. That’s the counterintuitive piece and also it is our biggest opportunity for higher GDP per capita, and therefore higher standard of living.

OK, but how do you increase labor productivity? I’m glad you asked. There are three primary ways, but only one has unbounded upside. Can you guess what it is?

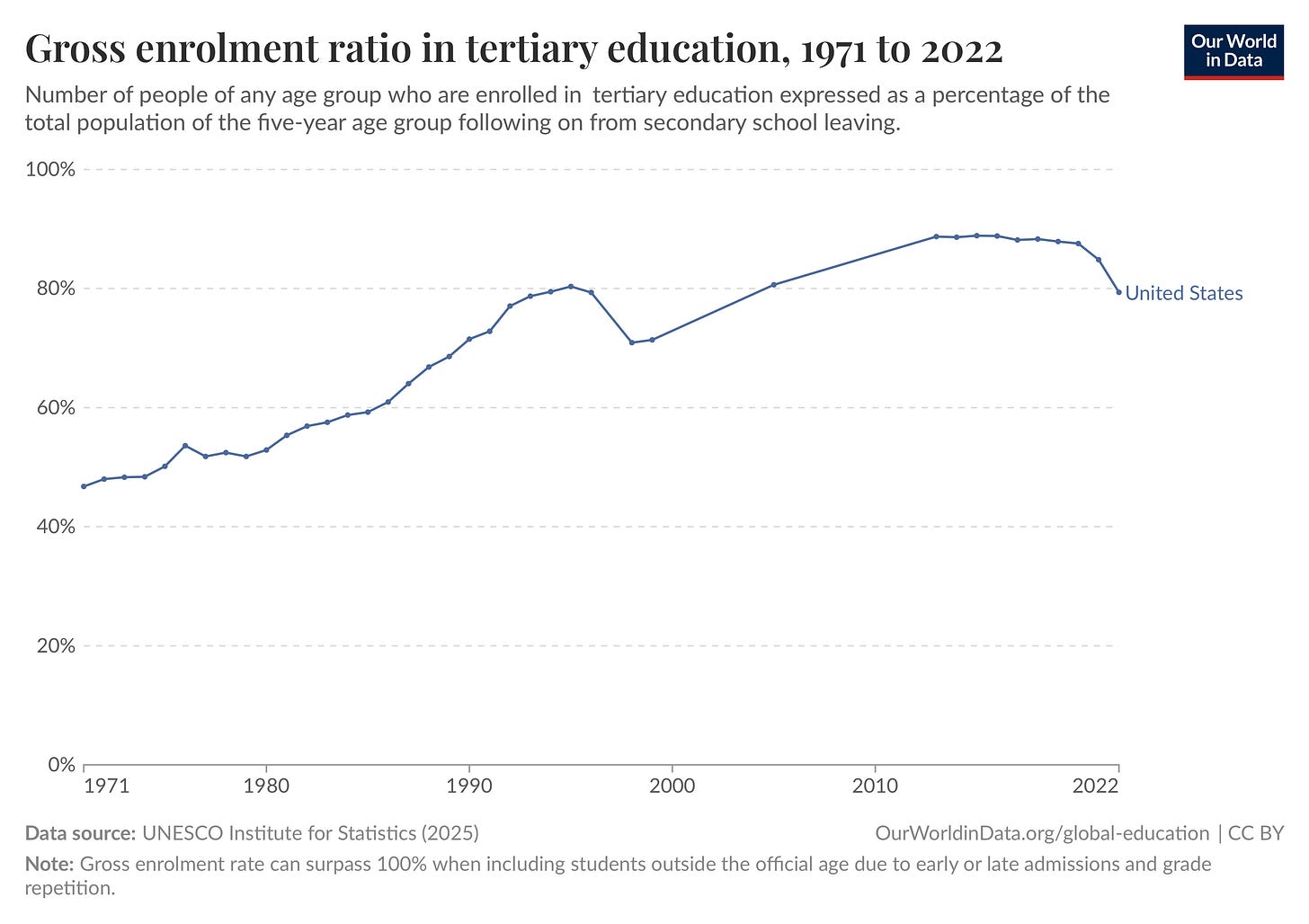

First, you can educate your workforce more, providing them with, on average, better skills to produce higher quality output per hour worked, a.k.a. investment in human capital. The U.S. is currently going in the wrong direction on this front when you look at the % of recent high-school graduates enrolled in “tertiary” education (which includes vocational programs).

If we had continued to make steady progress through the 2010s and 2020s, we would be headed towards diminishing returns on this front. While it will surely be good to increase this further to get those gains—and there is more you can do than just tertiary education such as on-the-job training—like we saw earlier with access to clean water, there is effectively a max out point for education in terms of its effect on GDP per capita. Think of a point in the future where everyone who is willing and able has a college degree, or even a graduate degree.

Second, you can buy your workforce more tools, equipment, and facilities to do their job more efficiently, a.k.a. investment in physical capital. This isn’t inventing new technology, just spending more money to get workers access to the best existing technology. Again, you clearly reach diminishing returns here too, that is, another max out point, as you buy everyone the best tech. Think of the point where everyone has a MacBook Pro with dual Studio Displays—or whatever the equivalent is in their job—to maximize their productivity.

Third, and the only way that doesn’t have a max out point, is to invent new technology that enables workers to do more per hour. These are better tools than the existing tools on the market. Think of upgrading to the latest software version with updated features that make you a bit more productive. Or, more broad-based:

Think of how worker productivity increased in construction with the introduction of power tools and heavy machinery or in offices with the introduction of computers and the Internet. We need more of these, many times over: true leaps forward in technology applications that will dramatically increase our worker productivity. (The Great Race)

AI is likely one of these leaps, but by investing much more in basic research we can make higher labor productivity growth more continuous instead of the bumpy road it has recently been on.

These leaps don’t come out of nowhere. They require decades of investment in research, and that investment requires a decent level of government investment at the earliest stages. This was the case for AI, as it was for the Internet, and as it is for life-saving drugs.

This is actually good news, since it means we have a lever to pull to increase labor productivity that we’re not currently fully pulling: increase federal investment in basic research. The level we’ve ended at today is somewhat arbitrary, an output of a political process that wasn’t focused on increasing standard of living. In any case, I estimate at the bottom of this post that we’re off by about 3X.

If you want another view on this topic, here is a good post from the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

[I[mprovements in living standards must come from growth in TFP [Total Factor Productivity] over the long run. This is because living standards are measured as income per person—so an economy cannot raise them simply by adding more and more people to its workforce.

Meanwhile, economists have amassed lots of evidence that investments in capital have diminishing returns. This leaves TFP advancement as the only possible source of sustained growth in income per person, as Robert Solow, the late Nobel laureate, first showed in a 1957 paper.

TFP growth is also the answer to those who say that continued economic growth will one day exhaust our planet’s finite resources. When TFP improves, it allows us to maintain or increase living standards while conserving resources, including natural resources such as the climate and our biosphere.

Or, as Paul Krugmam put it even more succinctly in his 1990 book The Age of Diminished Expectations:

Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker. —Paul Krugman