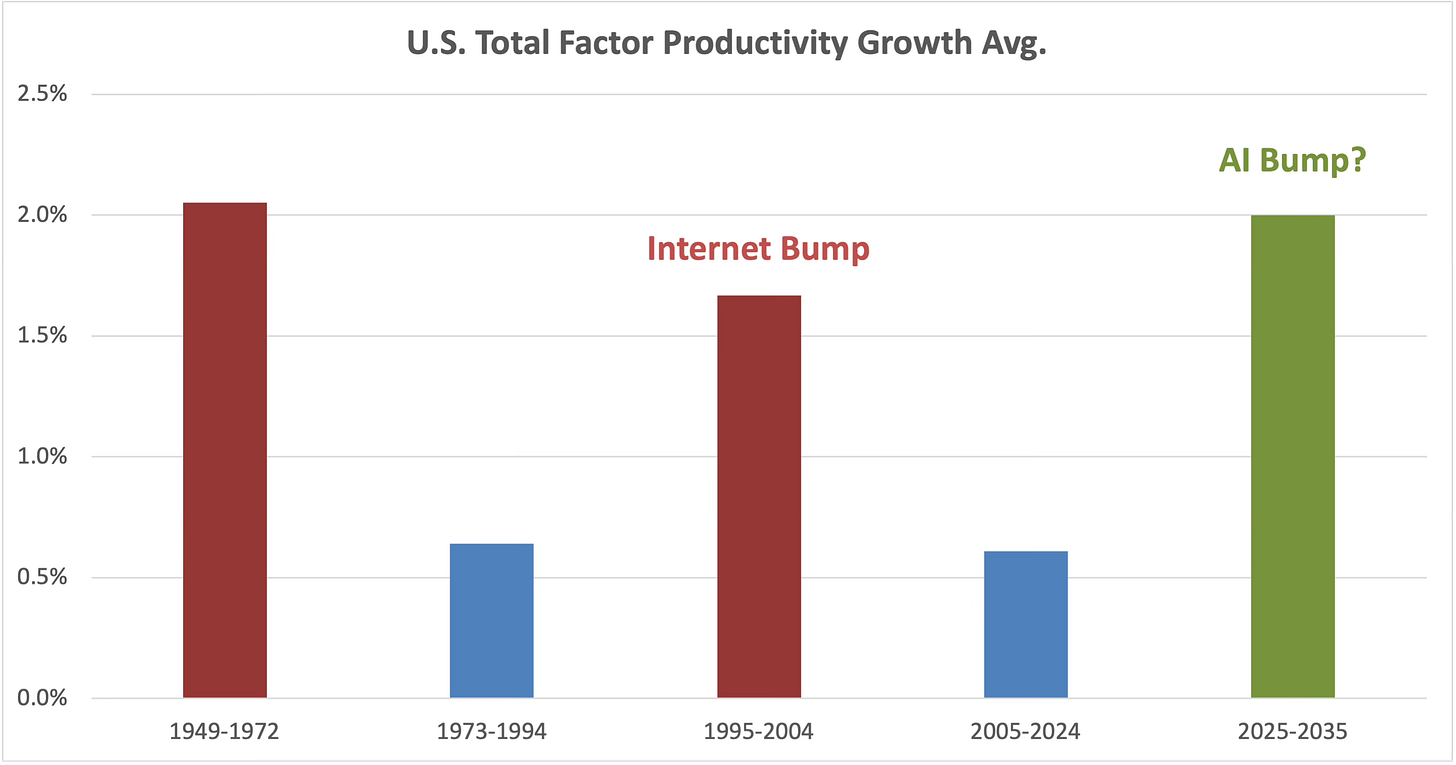

The debate over a potential economic bump from AI points to a much larger economic opportunity.

We can turn temporary economic productivity bumps into permanent higher economic growth through sustained higher investment in basic research.

The decade surrounding the Internet boom saw a marked increase in U.S. total factor productivity (TFP) growth—the economic efficiency gains beyond just adding more workers or capital—similar to higher levels seen before 1973. However, it then declined again from 2005 onward back to doldrums levels, which brings us to the present. Now, people are starting to debate a similar potential AI productivity bump unfolding over the next decade.

However, this debate raises an even bigger question: How do we achieve sustained higher productivity growth forever, not just in occasional blips and bumps? I believe this is the most important economic question because higher productivity growth is the key factor that drives long-term higher standards of living. Here’s a concise, understandable explanation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics as to why:

How can we achieve a higher standard of living? One way might simply be to work more, trading some free time for more income. Although working more will increase how much we can produce and purchase, are we better off? Not necessarily. Only if we increase our efficiency—by producing more goods and services without increasing the number of hours we work—can we be sure to increase our standard of living.

To continuously produce more without increasing the number of hours worked per person, we need to continually develop better tools. To continually develop better tools, we need access to increasingly better science and technology. To get access to increasingly better science and technology, we need sustained higher investment in basic research.

Think of how worker productivity increased in construction with the introduction of power tools and heavy machinery or in offices with the introduction of computers and the Internet. We need more of these, many times over: true leaps forward in technology applications that will dramatically increase our worker productivity. (The Great Race)

That is, to ensure higher productivity growth, we must continually invest sufficiently in the next set of technologies that will generate and sustain these higher productivity levels. That requires increased investment in basic research. But, why can’t private industry do it all?

The private sector…is excellent at taking established scientific breakthroughs and turning them into products over a few years. That’s because there is a clear profit motive in doing so. However, it is not as great at coming up with those scientific breakthroughs in the first place or commercializing them on much longer timescales like decades, where the profit motive is significantly reduced. This activity still generally involves some government-funded research in the early stages. (The Great Race)

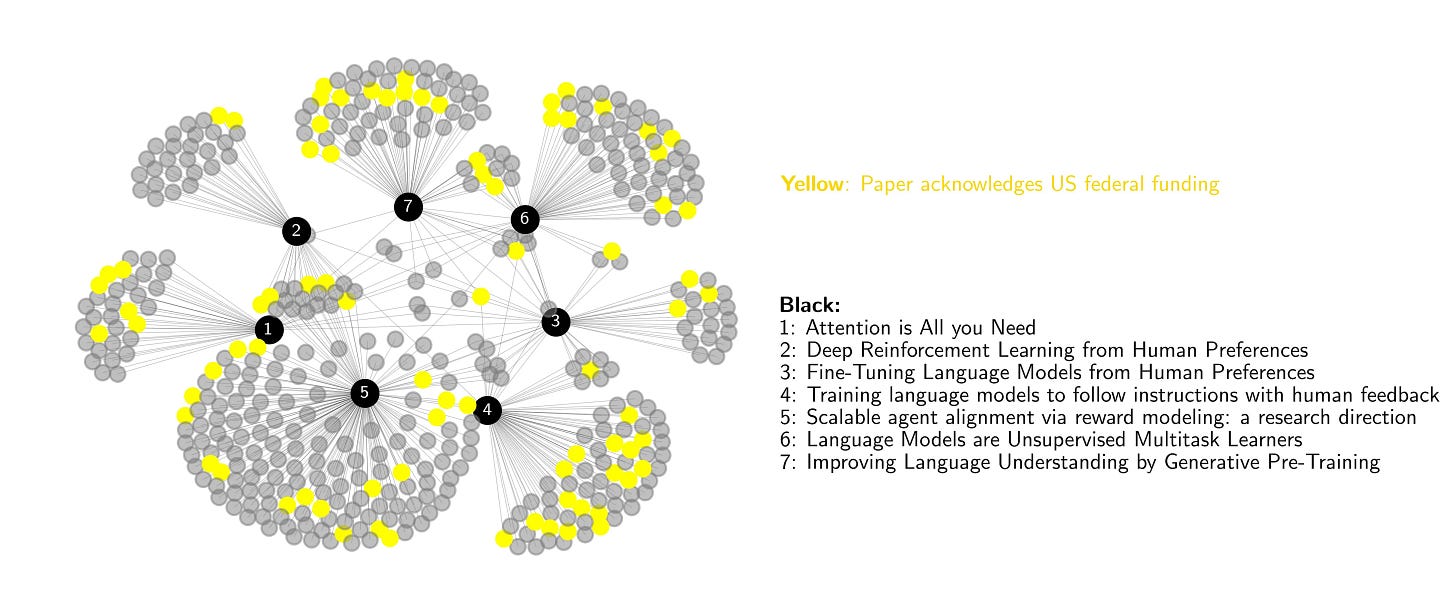

Yes, this includes AI too. A good post on this by Mark Riedl titled Visualizing the Influence of Federal Funding on the AI Boom takes seven key papers in AI, including Attention is All You Need (2017), and then traces which of their references explicitly acknowledge federal funding.

~18% of papers referenced by these 7 industry papers have acknowledged US federal funding.

~24% of papers referenced have US university authors.

~20% of papers referenced are industry lab-authored.

~42% of papers referenced do not have any industry authors.

The AI boom did not happen in an industry vacuum. As with all research, it was an accumulation of knowledge, much of which generated in university settings. There is a growing narrative that academia isn’t important to AI anymore and US federal funding has no role in the AI boom. It’s more correct to say that the AI boom could not have happened without US federal funding.

The same was true with the Internet boom. The same is also true in healthcare, for example, tracing federal funding through the most transformational drugs.

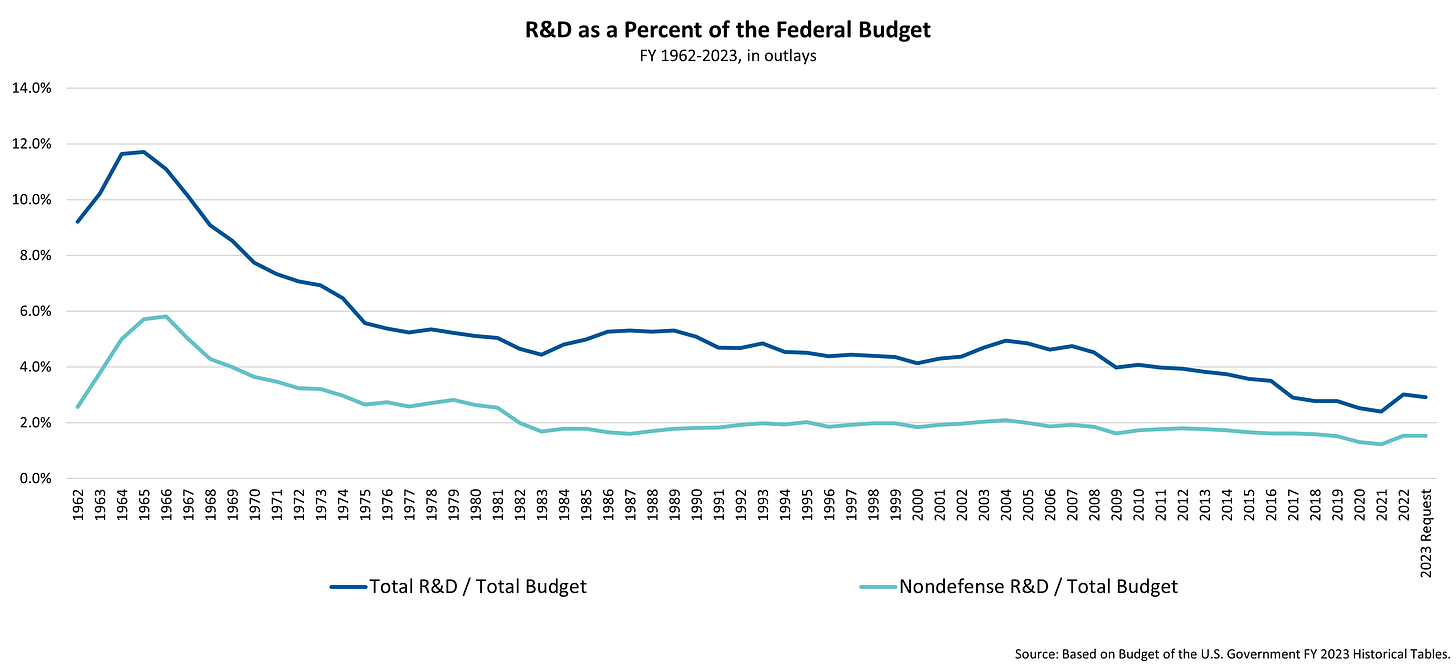

And yet, as I previously explored, science funding was already way too low before recent cuts. Quite simply, since the 1960s, we haven’t invested sufficiently in basic research to create sustained higher productivity. But we could change that.

And, as I've also previously detailed, this should be a no-brainer since, if done right, it literally pays for itself by expanding the economy, generating higher tax revenues, and ultimately lessening the debt-to-GDP ratio.

So while economists debate whether AI will boost productivity by 0.5% or 1.5% for the next decade, we should be asking: How can we better invest in basic research today to ensure we’re still growing faster in 2050? Short-term productivity bumps are a boon. But, if we want sustained productivity gains, we need sustained productivity investment.